Axe

Copyright © 2012 Terry Grimwood

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in Canada by Double Dragon eBooks, a division of Double Dragon Publishing Inc. of Markham Ontario, Canada.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from Double Dragon Publishing Inc.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Double Dragon eBooks

PO Box 54016 1-5762 Highway 7 East

Markham, Ontario L3P 7Y4 Canada

http://double-dragon-ebooks.com

http://double-dragon-publishing.com

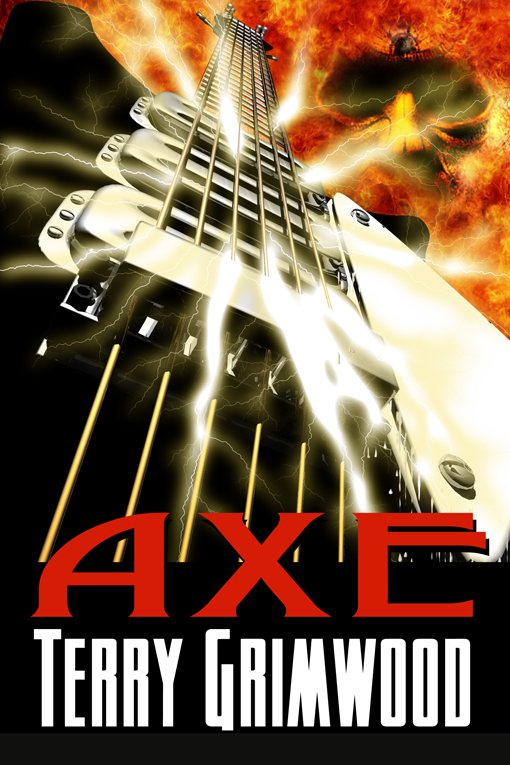

Cover art by Deron Douglas

ISBN-10: 1-55404-965-2

ISBN-13: 978-1-55404-965-3

First Edition May 4, 2012

PROLOGUE

Jack Fosdyke, otherwise known as Joe-Jack on account of his stammer, stubbed out his cigarette, swung his feet from the counter and said, "Cuh ... cuh ... can I help?" in the softest voice his nicotine-roughened throat would allow.

The middle-aged woman, hesitating at the door of Jack's Axe, looked up sharply. "Yes ... I hope so," she said. Her accent was neutrally correct.

She wore an expensive-looking fawn coat with rain-darkened shoulders and carried a half-folded umbrella and a briefcase. The case, tatty to the point of shapelessness, jarred sharply against the woman's persona; which was middle class, affluent.

There was an awkward pause, the woman hovering at the door, Jack, now on his feet, waiting behind the counter. November rain drummed against the music shop's plate glass and blurred the facade of the kebab take-away on the opposite side of Ipswich's Orwell Street into a paint run of molten drab.

Jack could understand the woman's reticence. Jack's Axe was a musician's shop, every inch of available space taken up with the new and secondhand hardware of electric rock and roll. It confronted rather than welcomed, barred your way with keyboards and sound equipment, hemmed you in with drum kits and percussion, threatened you with guitars.

Guitars and more guitars, Jack's own instrument, his specialty and Great Love. They were all there; Les Pauls, Fenders, Yamahas, Gibsons, and Rickenbackers, acoustic and electric, original and copy.

Where there were no guitars, there were shelves laden with sheet music and how-to-play books; there were strings, plectrums, leads, plugs, pedal switches and boxes and boxes of secondhand CDs and vinyl. There were also posters and flyers, on the wall behind the counter, in the window; bands for hire, equipment for hire, musicians wanted for bands, bands wanted for musicians, forthcoming gigs.

Jack himself blended, chameleonlike, with his shop. Bearded, gaunt, his hazel eyes sunk deep into their sockets, his shoulder-length hair, gray-peppered, Joe-Jack was an old rock soldier, an ex-session man, as war-scarred as the briefcase in the woman's soft-gloved hand.

"I understand you buy second-hand musicware," the woman said.

Musicware? Like Tupperware, Jack supposed, and said, "I d ... d ... do," then hurried out from behind the counter to assist her. He took hold of the briefcase's carrying handle and for a moment they shared its weight. Jack caught a tantalizing waft of perfume.

He noticed that her makeup only partially hid the deep webbing of lines about her eyes and mouth. Her fortysomething years had been hard ones.

Yuh ... yuh ... yours and mine both, he told her silently.

Jack hefted the case onto the counter. Water droplets glistened on its scuffed black surface, some forming rivulets that ran, sweat-like, down its flanks. He drew it to himself, flicked open the clasps, made to lift the flap, then hesitated and glanced up at the woman. She was staring fixedly at the case. The intensity of her concentration unnerved him, so he opened it, quickly, tensing, but not knowing why.

The case contained a plump sheaf of paper. Jack reached in and drew a handful out. And found himself looking at a dog-eared, slightly yellowed A5 covered with musical notation written in black ballpoint. It took only a moment for him to realize that it was for guitar; rock riffs, blues figures.

Jack's concentration must have looked like suspicion because the woman was suddenly talking. "Look ... Look, I'll tell you the truth." There was a tremor of confession in her voice. "I'm in the middle of a divorce, moving out, taking my share." She stumbled to a halt, head bowed. "This is the last thing I have to deal with. I was putting it off." She laughed, a humorless, bitter sound. "I've been putting it off for years. I thought I'd be all right about it, but there are too many bad memories ... perhaps I should have burned it."

"I'm glad you didn't."

"Are you?" She stared at him, her eyes steady now. "Perhaps you wouldn't be if you knew who wrote it. Where it was found."

"Truh ... Try me," Jack said, his curiosity aroused. "Huh ... huh ... who did write it?"

"My brother Andy. Andy Crane."

"Cuh ... Cuh ... Christ," Jack snapped, and felt the paper slip from his suddenly nerveless fingers.

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

It was when Lydia Walker yelled "go to hell" from behind the locked door of her flat that Steve Turner knew he was in real trouble. This was his fault, of course. He had lost his temper, then tried sorry after she had told him to get out, but her back was turned. So he had left.

Now, two hours later, he was back, because wandering around the empty town had made him feel even worse, because his bedsitter had been silent, downbeat, and lonely. And because he was afraid that he was going to lose her.

"Lydia," he called through the unyielding, blue-painted door. "I'm not going away. I'm staying here, all night if I have to." His voice echoed around the first-floor landing, bouncing off the brick walls and concrete stairs. He wondered if any of Lydia's neighbors were listening.

"Did you hear me? I'm staying here."

No answer. There would be no more answers tonight.

Exhausted, Steve slumped against the door, forehead resting against wood. In the fifteen years since his divorce, he had forgotten how bad woman trouble could be. Fifteen years, without anything approaching a serious relationship. Until this improbable union between Steve Turner, earring-wearing building laborer and thirty-eight-year-old teenager, and Lydia Walker, graphic designer and twenty-six-year-old grownup.

Improbable and irreparable, he mused bitterly. Thanks to my temper.

Steve dropped to his haunches, leaned back against the cold brick wall of the landing, and ran his hand through his thick, sand-blond hair. So what was he going to do now?

Stay here, that was what, just as he had said he would. Not that Lydia had been impressed by his threat. But she would be. When she emerged in the morning to fetch in her milk and saw him there, cold, broken, and contrite, then she'd be sorry.

He got to his feet and after a moment's hesitation-just in case Lydia was about to throw open the door and rush into his arms-headed downstairs. If he was going to stay the night, he would at least need the barest of creature comforts as well as something to do to while away the long hours.

Outside, a harsh, damp wind was tearing through the slab-sided alleyways formed by the Henley Court flats. Icy rain slashed into Steve's face, forcing him to turn up the collar of his leather biker jacket as he ran, in a semicrouch, to his car, a fully restored 1976 Ford Cortina Mark 3 gleaming under the orange street lighting.

He opened the boot and pulled out the wool blanket he kept for emergencies, then picked up his guitar, safe in the new soft cover he had recently bought from Jack's Axe. He noticed the briefcase of handwritten sheet music he had acquired at the same time and hauled that out as well.

Back inside, he rang Lydia's doorbell one last time. There was no reply. He hadn't really expected one. He took off his jacket, rolled it up as a pillow, then sat down once more and wrapped the blanket around himself as best he could. Within minutes his buttocks were aching. He was cold. He was bored. He closed his eyes, opened them again, and knew that he wouldn't sleep.

He glanced at his guitar, which rested against the wall beside him. Then pulled it to himself, unzipped the cover and drew the instrument out, nestling its familiar weight and feel against himself. The fingers of his left hand automatically curled about its neck to form a low E. The axe was a Gibson SG (solid guitar), circa 1966-67, possibly older, finished in highly polished, heavily grained mahogany, and fitted with the Kluson machine-head and humbucker pickups that were standard features of the SG.

In his more sentimental moments, he considered it to be the best friend he had ever had; at other, more cynical times, the cause of all his troubles.

Take his marriage, for example.

Money had been Steve and Caroline Turner's biggest problem. Neither his job as a building laborer or hers as a shop assistant brought in a great deal of cash. Caroline had been the sensible one, of course, working miracles with their meager resources, paying the bills and even managing to save a little. Steve, on the other hand, was a dreamer, spending too many nights out with his part-time rock band, too little with his lonely, struggling wife.

He still felt guilty, even now, fifteen years later. Caroline had remarried of course. She was the marrying type.

So here he was, still mixing cement and carrying bricks for Burgess and Foulger, still living in the same tiny bedsitter, still knocking around with his band-they were called The Blue Dogs these days-and still dreaming of stepping into the giant footsteps left by the likes of Clapton, Townsend, and Hendrix. Though lately, things h...