A Concise History of Finland:

the 11th to the 21st Century

Soile Varis

ISBN 978-952-5901-38-2 (EPUB)

Copyright Soile Varis and Klaava Media

October 2012

Translated from Finnish by: Ari Hakkarainen

Editor: Petrena Barnes

Publisher: Klaava Media / Andalys Ltd

www.klaava.com

book@klaava.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of publisher.

Contents

1. The Era of Swedish Rule

2. Finland as a Pawn in Superpower Politics

Autonomy

Life in the Grand Duchy

3. The Rise of the Finnish Identity and National Awakening

National Awakening

Central Figures

4. The Turning Point in the Society and the Economy

The Reforms in the 1860s

Fennomans, Svekomans, and Liberals

Heading towards the Civil Society

Economy

The Changing Society

The First Period of Oppression (1899 – 1905)

Attitudes toward Russification

Parliament Reform in 1906

The Second Period of Oppression (1908 – 1917)

Jaeger Movement

5. Finland's Independence Movement

Independent Finland

The 1918 Civil War in Finland

Brief and Bloody Civil War

The Fight for a Constitution

German King

6. From Dichotomy to Unification

Young Republic

The Improving Standard of Living

Art as a Consumer Good

The Power of Entertainment

Left and Right Wing Radicalism

Expand Finland, Liberate Viena

Lapua Movement

Foreign Policy in the 1920s and 1930s

7. Finland in the Second World War

Towards the Winter War

105 Days of Fighting

Cease-fire Period

Continuation War

Withdrawal from the War

"The Years of Danger"

The Rise of the Left Wing

YYA Treaty 1948

Comprehensive War Reparations

Reconstruction

8. Building Up the Welfare State

Detent

Frozen Nights

Note Crisis

Fight for Neutrality

Trade Policy

Finlandization

Structural Change

Cultural Shift

9. Finland's New International Role

After Kekkonen's Period

From Soviet Union to Russia

European Union

Economic Recession in the 1990s

Finland and Globalization

1. The Era of Swedish Rule

In the early Middle Ages, Sweden and the Grand Duchy of Novgorod began to show interest in the territory of Finland. Each state intended to fold Finland religiously, politically, and economically into its own sphere of power. Sweden succeeded. In the era of the crusades (1150 – 1323), Finland was integrated into the Kingdom of Sweden, drawing Finland under the influence of the Roman Catholic Church.

The legend of peasant Lalli emerged in the era of the crusades, when he killed Bishop Henrik. Later, Henrik was appointed the first Finnish Saint. Painting by C. A. Ekman 1854.

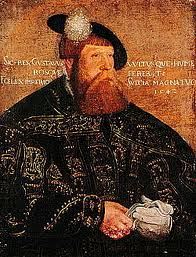

The Reformation, which had started in Germany, reached Sweden in the 16th century. King Gustav Vasa saw economic and political opportunities in the Reformation. He converted the people of the Kingdom, including the Finns, to the Lutheran Church.

In the 16th century, the Vasa family actively pushed the Kingdom's boundaries farther to the East. During the 17th century, Sweden had grown into a superpower of the Baltic Sea. Finland's armed forces, governance, and economy were changed as well. During the 18th century, Sweden lost its superpower status. Finland experienced difficulty during the Russian occupation.

King Gustav Vasa (1496 - 1560).

Finland inherited the Western culture and societal model from hundreds of years of Swedish rule. The state had been run mainly by Swedish nobility. Finns continued to cultivate their land as they had always done, including the time when they were part of the Russian empire.

2. Finland as a Pawn in Superpower Politics

Turbulent superpower politics in the early 19th century was the primary reason for Finland becoming part of Russia. France was growing into a European superpower that wanted to take over Great Britain.

In 1807, the emperor of France, Napoleon, and the emperor of Russia, Alexander I, met in Tilsit to plan an embargo of Great Britain. The plan, however, wasn't complete without Sweden. Sweden refused to join the embargo because Great Britain was a significant trading partner for that Kingdom. In order to put pressure on Sweden, Russia attacked Finland, starting The Finnish War (1808 – 1809). Sweden didn't react fast enough, allowing Russia to quickly conquer Finland.

Napoleon Bonaparte and Alexander I in Tilsit in 1807. A 19th century painting.

Despite its original plans, Russia decided to hold Finland. Ties with France had solidified. Russia was concerned that Sweden might try to recoup Finland, and the Finns might stand against the new rule. Autonomy was a way to ensure Finns were satisfied with the new ruler.

In 1809, Emperor Alexander I called upon the Diet in Porvoo, where he explained his new administration to the people. The emperor committed to retaining the status quo in Finland: Lutheran Church, Swedish language, laws, and privileges for the higher classes. The autocratic position of the ruler was retained as well, conveniently for the new ruler.

In 1809, at the Hamina peace treaty, Sweden officially gave up Finland.

Autonomy

Finland was established as a Grand Duchy with its own governance. The Imperial Senate of Finland, Parliament and civil servants formed the governing body. The Imperial Senate of Finland had the highest executive power. The Senate governed multiple central offices, such as the Board of Customs and the Post-Office Department.

The local representative of the emperor was the Governor General. He was the Chairman of the Senate and the Commander-in-chief of armed forces. The Minister of State relayed matters to the emperor in St Petersburg. Local administration in Finland remained unchanged. The emperor, the Grand Duke of Finland, was the highest authority. Russia was responsible for Finland's foreign policy. Russian troops were moved into Finland.

While Finland developed its autonomy; it became wealthier and its population increased. Taxes collected in Finland were used for Finland, in contrast to during the era of Swedish rule. Trading with Russia developed favorably. The customs border between Finland and Russia benefited Finland's economy as well. In 1812, Helsinki was determined to be the new capital of Finland. In 1828, the university was transferred to Helsinki from the old capital, Turku.

Helsinki Cathedral and the Senate Square were important elements for the image of the new capital.

In the early 19th century, Finland's society remained relatively unchanged. Parliament wasn't summoned for decades. After the Congress of Vienna and after Napoleon had been displaced in 1815, a period of reaction dominated the thought of European rulers, who were reluctant to consider new ideas or development. Civil servants governed Finland without the parliament. Censorship, restrictions on travel and control over the university were enforced. Europe's revolutionary years, 1830 and 1848, didn't affect Finland; Finns remained loyal to the emperor.

Life in the Grand Duchy

Upper classes retained their privileged status under the new government. Nobility benefited both from holding civil servant positions required by the administration and from career opportunities in the Russian army. The middle class prospered along with the increased trade with Russia. The clergy retained its privileges as well, staying loyal to the new rulers. The life of ordinary people didn't change, either.

In the 19th century, the majority of Finns lived in the countryside.

In the early 19th century, Finland was a poor country, with only small towns here and there. A peasant could own land, but his livelihood was meager. Industrial activity was scarce. The state closely managed business activities and economic policies according to the economic principles of the time. There was no single currency. Both the Swedish rigsdaler and the Russian rouble were in circulation.

3. The Rise of the Finnish Identity and National Awakening

National Awakening

In the early 19th century, nationalistic and national romantic ideas reached Finland. The educated class took an interest in the language and culture of ordinary people.

The efforts by Adolf Iwar Arwidsson for increased political freedom and for improving the status of the Finnish language in the newspaper, Åbo Morgonblad, were not welcomed in the 1820s. The newspaper was shut down, and Arwidsson was deported to Sweden. Nonetheless, Russia's attitude to the Finnish language and folk culture was positive, because they were considered to have the effect of weakening connections to Sweden, and allowing the Russian language to get a stronger hold on the country. In its early days, the movement toward nationalization didn't have any political objectives.

Central Figures

Finnish culture developed as a positive force in the early 19th century. The Finnish Literature Society and The Saturday Club (Lauantaiseura) were established.

The national epic of the Finns, Kalevala, compiled and written by Elias Lönnrot in 1839, strengthened the Finnish people’s faith in their own language and culture. Books, like Saarijärven Paavo and Vänrikki Stoolin tarinat by J.L. Runeberg, represented Finnish people in an ideal light, increasing interest in the peasant culture.

The national epic of the Finns, Kalevala, compiled and written by Elias Lönnrot in 1839, strengthened the Finnish people’s faith in their own language and culture. Books, like Saarijärven Paavo and Vänrikki Stoolin tarinat by J.L. Runeberg, represented Finnish people in an ideal light, increasing interest in the peasant culture.

J.V. Snellman introduced sociological and political views to the dialog about the Finnish identity.The key objective of the Finnish nationalists (known as Fennomans) was to get Finnish adopted as an official language in the country. Snellman introduced a plan that was intended to give birth to the idea of the Finnish culture as unique.

Before that recognition happened, however, the life of ordinary people would have to be improved. Snellman insisted that Finnish-language schools would have to be established and Finnish literature needed to be published. The university would have to teach in Finnish, and civil servants would have to learn Finnish. Snellman published his educational and practical objectives in the newspapers Saima and Maamiehen Ystävä.

4. The Turning Point in the Society and the Economy

The Reforms in the 1860s

In 1855, reformist Alexander II was appointed the czar of Russia. The Finns' loyalty to the czar during the years of revolutions in Europe and in the Crimean war (1853-1856) was rewarded. In 1863, Alexander II launched a reform plan that started to dismantle the class-based society.

The Diet of Finland was regularly summoned. Finnish was declared an official administrative language along side Swedish and Russian. The elementary school system was started, and municipal administration was separated from that of the church. Finland's autonomy developed further with regular Diet meetings, which increased political activity and interest in social affairs. The framework for a civic society started to take shape.

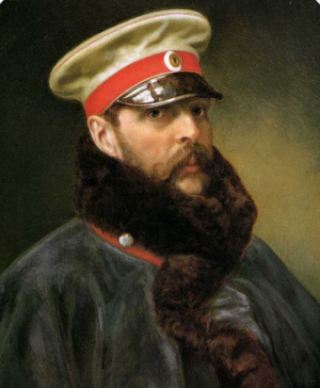

Czar Alexander II (1818 - 1881).

Fennomans, Svekomans, and Liberals

The first political groups were established in Finland in the 1860s. The key differences between the groups were related to language and culture. Continuous language conflicts drove the groups to form the first political parties that focused on language issues in 1870.

Fennomans consisted of peasants, the ministry, and students. Their mission was derived from Snellman's thoughts. Svekomans brought together educated Swedish-speaking people, nobility, and the middle class. They believed only Swedish-speaking people were capable of advancing civilization. Their goal was to maintain the situation as it was. Liberals believed reforms in the society were more important than the language.

The newspaper Uusi Suometar was the public voice for the Fennomans. Soon the Nuorsuomalaiset group separated themselves from the Fennomans. The Nuorsuomalaisets established the newspaper Päivälehti, which developed into Helsingin Sanomat in 1904. Helsingfors Dagblad was the Liberal's newspaper, as also briefly was Hufvudstadsbladet. Svekomans were supported by the newspaper Vikingen.

Heading towards the Civil Society

The initiative by Alexander II and active work by Snellman produced a new law that defined the elementary school system in Finland. The principle was to establish schools that were free to all children. The process for opening enough schools was slow, however.

The language conflict didn't help the development of the secondary school system. Financed by private funds, the Fennomans established the first Finnish-language secondary school in Jyväskylä.

Finnish school children at the end of 19th century.

In 1865, a law was passed that gave local communities self-governance rights. In the countryside, people without their own land were not eligible to participate in local communities' decision-making. The self-governance of towns was reformed as well. Every taxpayer could vote according to the amount of taxes paid. The impact of the reform was significant. Ordinary people could have a say in decision-making in the society.

As the European nationalism, liberalism, and labor movements developed, Finns also adopted those ideas. The ideas increased interest in politics. Since not all citizens had the right to vote, associations emerged as a channel to influence solutions to problems in the society. At the end of the 19th century, new associations were actively set up. The Association of Public Education, KVS (Kansanvalistusseura), taught literature, music, theater, and reading. The Association of Finland's Women (Suomen Naisyhdistys) improved women's rights in the society, as well as their economic and political status. The Temperance Movement (Raittiusliike) grew into the largest public movement in Finland, andmanaged to pass the Communal Prohibition Act.

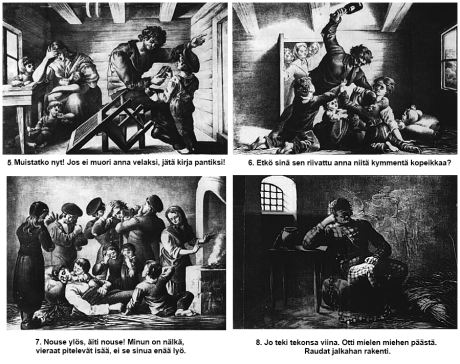

A story with a lead character called Turmiolan Tommi depicted damages caused by alcohol. Sobriety education in Finland in the 19th century.

The labor class established associations that focused on education. In the 1890s, the movement adopted principles from socialism, driving business owners away from the movement. In 1899, the Finnish Labor Party (since 1903 the Social Democratic Party of Finland) was established.

Economy

Alexander II wanted to modernize Russia and push Finland into the ongoing industrial revolution. Mercantilism was replaced by economic liberalism, diversifying Finnish business and trade. The freedom to conduct business was approved in 1879. Craft guilds were disbanded, restrictions on steam sawmills were removed, and stores could be opened in the countryside as well.

Finland was allowed to have its own currency, the Mark (markka), stabilizing the monetary situation. The Finnish Mark was tied to the gold standard, stabilizing its value and preventing inflation. The number of commercial banks and corporations, and the amount of foreign investment increased in Finland at the end of 19th century. Banks contributed to the availability of capital and the ability to start new businesses. Citizens were free to move to places where work was available, boosting business and the economy.

The industrialization of Europe increased demand for timber, making it the most important export product from Finland in the mid-19th century. Finland's wood-processing and paper industry benefited from low-cost labor and a vast supply of raw material. The metal industry's development was boosted by industrialization and automation. In the early 19th century, the most significant industrial town was Tampere, where Finlayson established a textile factory.

James Finlayson (1771-1852), the Scottish industrial entrepreneur, established a factory in Tampere.

Both industry and trade required railway transportation. The first track was built from Helsinki to Hämeenlinna in 1862. Next, tracks were laid to St. Petersburg and to Tampere. Trade routes with St. Petersburg and connections to the Baltic Sea were further improved after the Saimaa Canal was opened up. The telegram, telephone, and electricity started to change the daily life of Finns. The demand for consumer goods increased.

The thriving economy improved the standard of living both in towns and in the countryside. In the 1860s, a number of famine years forced Finns to diversify their farm production. Dairy production increased, and automation of work started. The growth of the forest industry increased land owners' income, because they could sell timber to the factories.

The Changing Society

Driven by the economy, reforms, and active civil movements, the structure of the Finnish society had reached a turning point. Industrialization encouraged citizens to migrate to towns, drove the development of cities, and caused emigration. The majority of emigrants moved to the United States, Canada, and Russia.

Roles of the lower and upper classes began to shift as the assets owned by a family were regarded to be more significant than the family's origins. The differences between citizens reached a peak at the end of the 19th century. The number of people living in the countryside without their own piece of land was increasing. Particularly, 50,000 tenant farmers who leased their farmland were in a difficult judicial and economic position. With minimal political power, the working class felt mistreated as well.

The First Period of Oppression (1899 – 1905)

At the end of the 19th century, Russia tightened its grip on its borders, including Finland. Fanatic Slavophiles demanded the conversion of the multinational country into a single Russian state, while reformists demanded modernization of the society.

Russians were provoked by Finland's customs border, the inability to appoint Russians as civil servants, and because only a few Finns spoke Russian. Russians were also concerned about Europe's superpowers, which were forming alliances. Germany, which was united in 1871, was regarded as a threat as well. The envisioned risk was Germany's potential support to the countries along Russia’s borders. These border countries might attempt independence, threatening the safety of the capital, St. Petersburg.

Russia began to "Russify" Finland. According to the program, the Finnish army would have to integrate with the Russian army, Russians would be appointed to administrative positions, and the laws of the two countries would have to be unified. The Diet refused to approve the law for compulsory military service. This situation culminated in the February Manifesto of 1899, issued by Nicholas II, which started the first period of oppression, from 1899 to 1905.

Czar Nicholas II (1868 - 1918) with his family.

The new legislation allowed Russia to set general laws, while The Diet of Finland was limited to issuing statements concerning the planned laws. Finland's Post Office was closed down in 1890. Russia was declared the official language for administration. The Finnish army was disbanded. In 1904, Finland’s people were relieved from compulsory military service because of strikes during conscription. Finland had to pay additional military taxes.

The unification process led to censorship, newspaper closures, the firing of civil servants, and deportations. Finally, Finns awoke to defend their autonomy. Two petitions, the so-called Great Address and Pro Finlandia were delivered to Nicholas. The Czar ignored them.

Many Finnish artists opposed Russian activities as well. The national Romantic Art movement supported the Finnish people’s political demands and improved the Finns' self-esteem. Some of the most significant artists from the Golden Age of Finnish Art were Albert Edelfelt, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Eliel Saarinen and Jean Sibelius.

Composer Jean Sibelius (1865 - 1957) opposed the Russian oppression.

Attitudes toward Russification

Russia's unification policy split the political movements in Finland into those who were compliant (traditionalists), supporters of the constitution (Swedish party, labor movement), and activists (the educated Swedish-speaking class). The compliant group wanted to retain good relationships with the emperor. Oppression had to be tolerated in order to retain the Finnish culture. The constitutional group regarded this "Russification" as oppression against the constitution, and refused to obey the new rules. They conducted passive resistance. Activists were ready for violence. The labor movement objected to “Russification” as well, but regarded reforms in the society to be even more important objectives.

In 1904, after Finnish activist Eugen Schauman murdered Russian governor-general Nikolai Bobrikov and committed suicide, the situation was critical. The next year, a general strike in Russia spread to Finland as well. Finally, Nicholas II approved the demands for reforms in order to end the disturbances. The so-called November Manifesto ended the “Russification” activities.

Parliament Reform in 1906

Thanks to the November Manifesto, Finland's Parliament could be reformed into the most modern parliament in Europe. Democracy took over when the old Diet was replaced by a 200-seat unicameral Parliament. Now, ten times as many citizens had the right to vote. Every 24-year-old citizen had the right to vote, including women. However, the new election system did not apply to the municipal elections.

Some of the women elected as Members of Parliament. Women got the right to vote in Finland in 1906.

The new system forced political parties to organize themselves and to conduct active campaigns for the elections. In 1907, the first Parliamentary elections were organized in Finland. The right wing won the majority of the 200 seats. Social Democrats won 80 seats. The emperor still had the right to dissolve the Parliament.

The Second Period of Oppression (1908 – 1917)

In 1908, the oppressive movement to form a nationally united Russia resurged. Laws concerning Finland were submitted to the council of ministers before passing them on to the emperor. The power of Russian civil servants over Finland's administration increased. The Parliament didn't approve the changes.

The pace of unification activities was speeding up. In 1910, Russia ordered all matters, excluding Finland's internal affairs, to be sent to the Russian State Duma. In 1912, the Equal Rights Law guaranteed civil rights for Russians, who could also work as civil servants, and who could conduct business in Finland.

Finland's "Russification" was set to be completed in 1914. However, the plan wasn't put into action because the First World War broke out. Finland was declared to be in a state of war.

Russia's poor showing in the war, and its severe internal problems, created a crisis. In March 1917, revolution broke out. The emperor was dethroned. The "Russification" activities were cancelled, ending Finland's Second Period of Oppression.

Jaeger Movement

The plans for Finland's total "Russification" had prompted students to establish the Jaeger movement. The objective for Jaegers was to form an army of its own and to separate from Russia. About 2,000 Finns, from many classes of society, traveled to Germany for military training. Germany supported the independence plans of the countries on Russia's borders in order to weaken Russia. In Germany, Finns formed the Royal Prussian Jaeger Battalion No. 27. The Battalion was to have a significant role later in Finland's history.

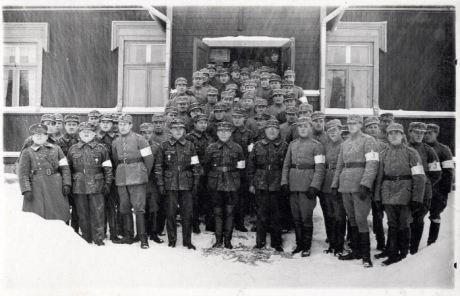

Finnish Jaegers were trained in Germany.

5. Finland's Independence Movement

Independent Finland

The fall of the emperor in March 1917 (The February Revolution) and the establishment of a temporary government in Russia caused a power conflict in Finland. Social Democrats, the Agrarian Party, and other activists believed the Parliament was the highest authority. The right wing's argument was that Russia's temporary government had inherited the highest power from the Czar.

Six representatives from the right wing parties and six Social Democrats were elected to the new senate. In July 1917, the Social Democrats, who had the majority of the seats in Parliament, managed to pass a law determining that the highest authority in Finland was the Parliament. Russia's temporary government responded by disbanding the Parliament. The right wing parties won the majority of seats in the new elections.

In November 1917, Bolsheviks led by Lenin dethroned Russia's temporary government (October Revolution). The Social Democrats wanted to co-operate with the Bolshevik government, while the right wing wanted a rapid separation from Russia. The situation was tense. In order to support the demands of the working class, the Social Democratic Party arranged a general strike in November. It resulted in new laws, such as an eight-hour workday and general and equal voting rights in municipal elections.

The Parliament, in which the right wing parties had the majority, declared itself the highest authority in Finland on November 15, 1917. The majority of the new government, led by P.E. Svinhufvud, consisted of right wing party members. The declaration of independence was affirmed in Parliament on December 6, 1917. Finland sought recognition for its independence from foreign states, but the world was waiting for Russia's actions. Soviet-Russia recognized Finland on December 31, 1917.

The 1918 Civil War in Finland

In the early 20th century, social and political problems had developed to a critical state in Finland. The conditions of the working class and the rural poor were unacceptable. Reforms by the Parliament and Senate appeared to take far too long, making the working class doubt democracy. Rapid inflation, strikes, and unemployment increased their anger. In 1917, a poor supply of food caused famine in some regions.

Revolutionary ideas spread among the working class. Finns chose their sides, splitting into socialistic (Reds) and right wing (Whites) groups. During 1917, both sides formed armed-guard troops that had violent fights. Finland didn't have an army of its own, nor did it have operational police forces. 40,000 Russian soldiers were still based in the country, increasing the feeling of insecurity.

Guards of Whites consisted of land owners and the middle class.

In January 1918, the Senate declared that the White guards were the government's armed forces. The labor movement's committee mobilized the Red troops, ordering them to take over key administrative offices in Helsinki on January 27, 1918. The Senate fled to Vasa, where the newly appointed leader of the White troops, C.G.E. Mannerheim, was also located. Mannerheim and his troops disarmed 5,000 Russian soldiers.

A White government led by P.E. Svinhufvud was formed in Vasa. The Red government was based in Helsinki, led by Kullervo Manner. The Red government's objective was to introduce socialism to Finland and to empower the working class. The objective of the White government was to ensure that Finland remained independent.

Brief and Bloody Civil War

The Reds were primarily supported by the industrialized Southern Finland, whereas the Whites were supported by the farming region of Ostrobothnia. Independent farmers and the middle class were fighting for the Whites. Laborers living in towns and the rural poor fought for the Reds.

The main front was formed along the Pori-Tampere-Lahti-Viipuri axis. In February 1918, the Reds attacked towards the North, but failed. Svinhufvud turned to Germany for help. Germany accepted the request after it had secured favorable economical and military terms from Finland. In February 1918, about 1,000 Jaegers returned to Finland from Germany to fight for the Whites.

The key battle was fought in March, when the Whites conquered Tampere. The Red government fled to St Petersburg. In April, the Whites received reinforcements from Germany -- 10,000 men and naval forces. German troops disembarked at Hankoniemi and swiftly conquered Helsinki. The Whites arranged their victory parade about three months after the war had started, on May 16, 1918.

The total number of deceased during the war was about 40,000 people. Both sides conducted acts of terror. The losers of the war were mistreated. 80,000 Reds were assembled and placed in prison camps, where 12,000 died of diseases and hunger. Heavy punishments to losers increased bitterness against the Whites, straining relations until the 1930s.

After the civil war, the lost side was assembled in prison camps.

There are many different opinions of why the war broke out. The different ways that Finns of different backgrounds still view the traumatic war of 1918 is reflected in the names given to the conflict. The Whites called it a War of Freedom, while Reds called it a Class War. Both sides have also called it a Revolt. Some additional terms used are the Fraternal War and the Red Revolt.

The Fight for a Constitution

The bloody Civil War had interrupted the process of confirming Finland's republican constitution. The war turned a number of right wing politicians into monarchy supporters. They believed monarchy would be stronger and could prevent the kind of turbulence they had experienced.They felt a monarchy could also rise above conflicts between political parties.

The Finnish Party and the Swedish People's Party of Finland supported monarchy. The Young Finnish Party didn't have a single view. A republic was suppo...